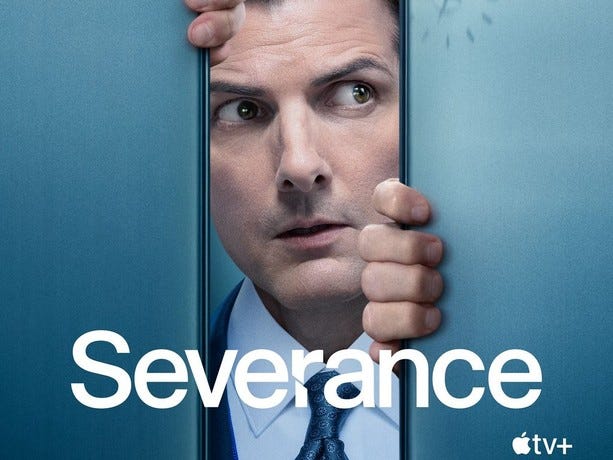

Severance and the Fractured Self: A Reflection on Life, Work, and Identity

Severance is arguably one of the best television series ever made, and it comes with a lot of hidden meaning along with tons of detail, let's dive in.

Like a lot of people, I’ve been completely sucked into Severance - this eerie, mind-bending masterpiece that feels like it was made for people who love the slow-burn mystery of Lost but also want something even more unsettling. The cinematography is pure art. The writing is as Sharp as a scalpel and the entire concept is absolutely haunting. It’s one of those shows that doesn’t just entertain you…it lingers, gnaws at your thoughts, and makes you rethink everything about your own life.

But what’s really sticking with me isn’t just the mystery of Lumon Industries or its cult-like corporate weirdness. It’s how Severance forces us to confront something much closer to home: the way we already compartmentalise ourselves, the way work consumes identity, and the quiet existential horror of living on autopilot.

A Fictional Nightmare That Feels Too Real

We like to think of work-life balance as a goal - something we can achieve by setting boundaries, working remotely, or maybe even chasing that ever-elusive dream job. But Severance takes this idea to its most extreme conclusion: what if you could completely separate work from life? What if you could clock in, disappear, and never feel the weight of your job outside of those hours?

On the surface, that sounds appealing. No late-night stress, no creeping dread on Sunday evenings. But then the show asks: What happens to the version of you left behind? The one trapped in an endless cycle of meaningless tasks, stripped of context, growth, or purpose. The one who exists only to work.

And suddenly, it’s not so far from reality. Because let’s be honest - how many of us already live versions of this? Checking out mentally during our commutes. Feeling like different people in different contexts. Turning work into something we endure rather than something we own.

Identity, Autonomy, and the Cost of Compartmentalisation

One of the most unsettling aspects of Severance is the idea that the outie (the version of you outside of work) makes the choice, but the innie (your work self) lives with the consequences. That split forces us to ask: How much of who we are is shaped by what we do?

In reality, most of us already wear different masks - one for work, one for friends, one for family. We switch gears constantly. But if we strip away all those roles, what’s actually left?

The show taps into something deeply real: our fear of losing autonomy. The innies in Severance don’t rebel just because they want to slack off - they rebel because they want agency. And isn’t that what we all want? Freedom. Control. The ability to choose something more meaningful than our paycheck.

What Severance Teaches Us About Real Life

At its core, Severance is asking a question we should all be asking ourselves: Are you living your life, or are you just passing time?

The characters in the show start out as passive participants in their own disconnection. But once they realise they’re sleepwalking through existence, they fight back. That’s the wake-up call. Not just for them - for us.

The real horror is you don’t need a sci-fi brain implant to split your life into disconnected pieces. Plenty of us do it every day without realising. The version of us that fakes enthusiasm on work calls. The one that switches off emotions just to get through the day. The one that postpones dreams because the routine feels easier.

The message of Severance isn’t just that the procedure is dystopian - it’s that we should never be so disengaged from our own lives that we would find it appealing in the first place. The goal isn’t to escape work, but to create a life where we don’t need that kind of separation. Where what we do aligns with who we are. Where we wake up every day knowing we’re actually living.

Because in the end, the real nightmare isn’t being trapped at work forever but waking up one day and realising you never truly lived at all.